This post, not sent to your email, shares some biblical reflections excised from today’s published newsletter cut to keep down the word count. I believe it is important stuff, but for a Reformation Day post I wanted to focus on the heart of the matter: listening to the voices of women proclaiming that the body of Christ is absent and empty.

When I first turned to the Gospel of John in 2022 for help making sense of spiritual abuse, my focus was fixed on chapters 9 and 10 about the man born blind and the Good Shepherd. As time went on I was drawn deeper into this bottomless Gospel, seeing more and more of the triune healing work of Father, Son and Spirit. Thankfully, that journey has not been a solitary one, and I have been immensely helped by others; not just books and articles, but friends in real time. I owe this week’s reflection to

and her comments this post which connected me to an immensely important source for John’s Gospel which was entirely unknown to me. That source is the Song of Songs.It’s hard to believe that was only 4 weeks ago. Since then I have devoured everything I can find on this connection between John and the Song, including

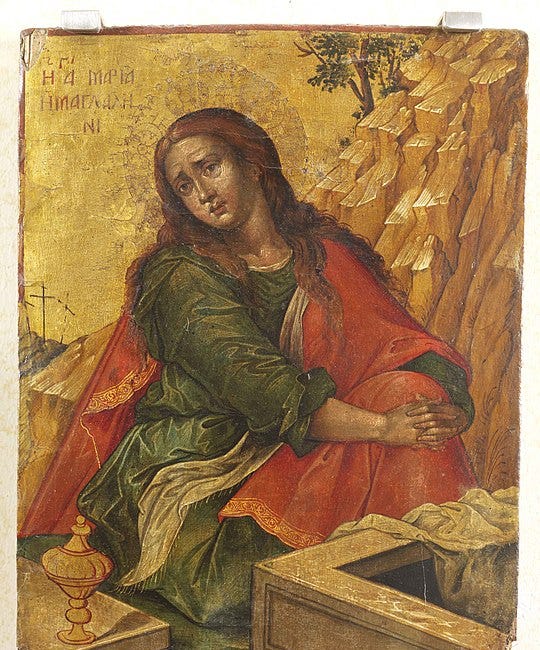

’s The Sexual Reformation, a handful of articles, a few lectures, found random related books at the local used bookstore like a commentary on John of the Cross’ A Spiritual Canticle of the Soul and the Bridegroom Christ, and ordered additional books, especially A King is Bound in the Tresses: Allusions to the Song of Songs in the Fourth Gospel by Ann Winsor Roberts (frustratingly delayed by shipping errors and arriving after this post reaches you).As Byrd says multiple times in her excellent book, John was a singer of the Song. For spiritual abuse survivors, the most poignant and most important example of this is Mary Magdalen’s story in John 20, which is also connected to the night scenes of the Song of Songs (ch. 3 and 5). Aimee Byrd wrote about these with terrible beauty in The Sexual Reformation (cf pp. 56-59 and pp. 142-151).

Reading, re-reading, and yet more re-reading of the Fourth Gospel has led me to increasingly symbolic readings. The darkness on the sea of Capernaum when “Jesus had not yet come” to the disciples was not just physical darkness (6:17). When Judas leaves the upper room to betray Jesus “and it was night,” it was so much more than merely the earth rotating out of view of the sun. When the disciples go fishing after meeting their risen Lord, it was night and “they caught nothing”; the night was likely as dark inside each one of them as it was outside (21:3).

So too with Mary in John 20:1:

Now on the first day of the week Mary Magdalene came to the tomb early, while it was still dark, and saw that the stone had been taken away from the tomb.

Like the disciples in the sea storm at night, this darkness is more than the absence of light. As Byrd puts it, “absence from the Bridegroom is darkness” (p. 143).

Of all 4 gospels, only John explicitly mentions that it was dark when Mary got to the tomb. I think the Song of Songs might help us see additional layers to that darkness, thereby helping us better receive the light of the risen Jesus.

While we don’t have explicit examples of this from the time of Jesus, the Jewish people read the Song of Songs during passover, and many scholars think that tradition was present in the 1st century.1 This would explain the connections between Song 3:11 and the crucifixion narrative of John 19 noted above. Adam Kubiś has made a compelling case that Song 3:11 is one of the key OT referents behind Pilate’s declarations “Behold the man!” (John 19:5) and “Behold your king!” (19:15).2 It is in this context that John is careful to tell readers, “Now it was the day of Preparation of the Passover. It was about the sixth hour” (John 19:14). The synoptic gospels never mention passover again after the institution of the Lord’s supper. What is up with this connection? Passover. Song of Songs. Crucifixion. The answer lies in why the Jews read the Song at passover. This will take us on a bit of a detour from the focus on Mary, but I believe it is worth it.

According to Benjamin Edidin Scolnic, some Jewish scholars believe that the original intent of the Song was to serve as poetic interpretation of the Exodus, “a series of readings in figurative language of the text of the Torah.”3

If the Song was read at Passover because of its connection to the Exodus, then it makes all kinds of sense for John to incorporate the Song into his gospel. References to Exodus, like the Song, are scattered throughout John for the careful, attentive reader. One of the clearest connections is John 3:14: “And as Moses lifted up the serpent in the wilderness, so must the Son of Man be lifted up” (cf Num 21:9). I believe darkness is also a key Exodus echo.

As I mentioned here, John’s extensive use of Ezekiel 34 makes Ez 34:12 a key verse for understanding darkness in John:

“so will I seek out my sheep, and I will rescue them from all places where they have been scattered on a day of clouds and thick darkness.”

The origin of this typology is found in Exodus when God redeems Israel out of Egypt. “Clouds and darkness” is Exodus language:

And there was the cloud and the darkness. And it lit up the night without one coming near the other all night. Then Moses stretched out his hand over the sea, and the LORD drove the sea back by a strong east wind all night (Ex 14:20-21)

This, of course, is when Israel is up against a wall, their backs to the Red Sea and their terror stricken faces facing the Egyptian army. Through Moses, YHWH parts the sea and brings his people through safely to the other side. Redemption accomplished. But the act of redemption is simultaneously an act of judgment, for YHWH used the waters to both save Israel and wipe out Egypt’s army:

“Thus the LORD saved Israel that day from the hand of the Egyptians, and Israel saw the Egyptians dead on the seashore” (Ex. 14:30).

Exodus sets the pattern for the remainder of redemptive history, and the prophets were especially fond of Exodus imagery. Jeremiah 23, which we’ve studied before, and is considered by some scholars to be the inspiration for Ezekiel 34, creates a sort of bridge between the Exodus and John’s gospel. Consider these verses, with relevant words in bold:

[11] “Both prophet and priest are ungodly; even in my house I have found their evil, declares the LORD. [12] Therefore their way shall be to them like slippery paths in the darkness, into which they shall be driven and fall, for I will bring disaster upon them in the year of their punishment, declares the LORD. (Jer 23:11-12)

Like the Egyptians being driven into the dark slippery path of the Red Sea, so too “if anyone walks in the night, he stumbles, because the light is not in him” (John 11:10).

Or consider Zephaniah 1:15 and 17.

[15] A day of wrath is that day, a day of distress and anguish, a day of ruin and devastation, a day of darkness and gloom, a day of clouds and thick darkness, [17] I will bring distress on mankind, so that they shall walk like the blind, because they have sinned against the LORD;

Why did Jesus say the Pharisees were blind? “If you were blind, you would have no sin, but now that you say, ‘We see,’ your sin remains” (John 9:41). There you have again the same themes occurring together: darkness, sin, blindness, oppression (cf Zeph. 1:9), and judgment.

Jeremiah likened the promised rescue of Israel out of exile to the rescue of Israel out of Egypt.

[7] “Therefore, behold, the days are coming, declares the LORD, when they shall no longer say, ‘As the LORD lives who brought up the people of Israel out of the land of Egypt,’ [8] but ‘As the LORD lives who brought up and led the offspring of the house of Israel out of the north country and out of all the countries where he had driven them.’ Then they shall dwell in their own land.” (Jer 23:7-8).

While the nations which took Israel into exile were certainly oppressive, it is the oppressive and ungodly prophets and priests of Israel which are likened to the ungodly Egyptians. Prophets, priests and kings alike, the unfaithful shepherds of Israel, “scattered my flock and have driven them away, and you have not attended to them” (Jer 23:2). And so they are destined to the same end as the host of Egypt: “Therefore their way shall be to them like slippery paths in the darkness, into which they shall be driven and fall” (Jer. 23:12).

Just as the exodus was, to put it simply, both spiritual and physical rescue, and just as the promised rescue of the prophets included both spiritual and physical rescue, so to does Jesus provide spiritual and physical rescue. In the Exodus, God rescued from the spiritually oppressive darkness of slavery along the Nile. After the exile, God rescued his people from the spiritually oppressive darkness caused by ungodly shepherds. In Jesus, God continues to do the same work, work which is given further depth and resonance with the traumatic night scene of Song 5. I believe that is connected at a typological/symbolic level with Mary Magdalen in John 20, which you can read about here:

Mary Magdalen and the Tears of Renewal and Reformation

This is part three of a mini-series focusing on the stories of women in the Gospel of John. In case you missed them, see part one regarding the woman of John 8, and part two regarding the Samaritan woman of John 4. Today the focus is on Mary Magdalen in John 20.

Jocelyn McWhirter. The Bridegroom Messiah and the People of God, p. 126.

Kubiś, Adam, “The Old Testament Background of ‘Ecce Homo’ in John 19:5” (Biblica et Patristica Thoruniensia 11.4 (2018)), p. 495.

Benjamin Edidin Scolnic, “Why Do We Sing the Song o f Songs on Passover?” (Conservative Judaism 48:4 (1996)), p. 59.

What an amazing time, in church history, to be alive. I'm so glad I found you, Aaron Hann. Your words are a gift to the church. Thank you.

One of the things I write about is the good & holy law given through Moses is darkness, and Christ is light. The Finer Points of Legalism

https://gospelrest.blogspot.com/2023/10/the-finer-points-of-legalism.html?m=1

Thank you again for writing about these women in John's gospel.