This is part 3 of a three-part series on John 11 and the story of Lazarus. In case you missed it, see part 1 and part 2.

If it’s true that “you are what you re-read,” as

put it recently, then John 11 is designed to turn us into lazarákia, or “Little Lazaruses.” Not the cute little rolls that Eastern Orthodox Christians bake to celebrate Lazarus Saturday, but like Lazarus himself. As we’ve explored, the story of Lazarus is artfully written so as to push readers to re-read multiple times. The end goal, as we’ll see today, is to embody this rereading to the point that we experience the spiritual liberation of Lazarus from religious trauma.I’m excited to explore this with you during Holy Week. As with part two, we’ll need to read John slowly and closely, and then consider some implications. I would love to hear your thoughts in the comments!

“Safe Spaces”

According to Mark Stibbe, “The tomb of Lazarus is the ultimate destination and the true object of focus in the story.”1 This may be true, but the complex movements of Jesus and the other characters on the way to the tomb signify more. This story has some strange dynamics in the way it navigates physical space. Have you ever wondered why Jesus doesn’t go all the way to Bethany, and why Martha and Mary leave their house to meet him? Where even is he for those encounters with the sisters of Lazarus? I believe trauma is the key to answering those questions.

Through a deep analysis of space and movement in John, Edward Wong suggests that space becomes haunted through association with “the Jews” and their dangerous presence. I would love to show you his analysis and explanation, but it would take too much time.2 We can see the signs of that haunting presence near the beginning, middle, and end of this story, where references to “the Jews” and Judea/Jerusalem signal danger (vv. 7-8; 18-19; 45-53).3 Instead of saying “Let’s go to Bethany,” where Lazarus died and was buried, Jesus said, “Let’s go to Judea” (v. 7). In an unnecessary narrator comment, John explains that “Bethany was near Jerusalem (less than two miles away)” (v. 18). The comment that “Many of the Jews had come to Martha and Mary” (v. 19) means that they came from Jerusalem. In vv. 45-53, the conflict between the religious authorities and Jesus comes to a climax with their determination to put Jesus to death. This decision takes place in Jerusalem, the very place from which “the Jews” travel to comfort Martha and Mary.

“The Place”

Ever since John 2:13-25, Jerusalem has been a site of conflict and increasing danger, and the subsequent movements of Jesus are marked by transitions to and from safe and unsafe spaces. It is this dynamic of haunted space that clears up the strangeness of Jesus stopping somewhere outside of both Bethany and Jerusalem. Wong explains,

“If a space can be assessed based on the risk of conflict and violence in post-traumatic contexts, then we are prompted to consider that the perception of safe/unsafe can function as an important element in the [Fourth Gospel’s] spatial framework.”4

If Jesus’ movements throughout John fluctuate back and forth between danger and safety, and if that very movement happens at the beginning and end of the Lazarus narrative (10:40; 11:54), I believe we can also see that dynamic within the narrative.

Jesus is twice described as being present in a “place” (v. 6 and 30, topos in Greek). While this at first appears to be insignificant, I believe there is more going on.

In v. 6 the “place” was the same as “the place” of 10:40: “So he departed again across the Jordan to the place (topos) where John had been baptizing earlier, and he remained there.” This appears to be “Aenon near Salim” in “the Judean countryside” (3:22-23).5

In 11:20, Martha meets Jesus, but the text doesn’t say where: “As soon as Martha heard that Jesus was coming, she went to meet him, but Mary remained seated in the house.” Later in v. 30 that location is recalled: “Jesus had not yet come into the village but was still in the place where Martha had met him.”

That language might sound unimportant, like a relative pronoun serving as a placeholder for another noun. But every other instance of “place” in John has symbolic significance. While Mary Coloe doesn’t comment on the first two instances in ch. 11, her summary observation is accurate: “The word topos [place] also has theological significance both in the Hebrew Scriptures and within this Gospel.”6 Topos is frequently used to refer to the temple and tabernacle in the OT, and John continues that typology. I don’t want you to just take my word for it. Consider the pattern of symbolic associations:

4:20 place = “the place to worship”, Jerusalem vs. Gerizim / Judea vs Samaria

5:13 place = synagogue

6:10 and 23 place = where Jesus does Moses-like wilderness feeding miracle

10:40 place = where John baptized

11:48 place = Jerusalem temple

14:2 place = Father’s house, place prepared by Jesus

18:2 place = temple-like garden where Jesus often met with disciples

19:17 and 20 place = where Jesus was crucified

Out of sixteen uses of topos, only those in 11:6 and 11:30 appear to be generic. The only thing in the immediate context to mark those locations as special or symbolic is the presence of Jesus. But there you have it: Jesus is the temple (2:19-21), so of course the “place” where Jesus was could be designated with a symbolically loaded word like topos. Ford calls this “the deep plain sense” of John’s language “which invites the reader to search for deeper meaning in plain words.”7

Why does that matter? Because of the presence of “the Jews” at the house in Bethany, that house was not safe. But the “place where Martha met Jesus” was safe. Grieving is difficult if not impossible in the haunting of traumatized space. Jesus creates a safe space where Lazarus’ sisters can meet with him and pour out their laments. But even still, “the Jews” follow Mary to “the place,” provoking Jesus anger at their questionable tears (as explored in part two), and possibly their questionable presence itself.8

As Stibbe observed, the tomb is the ultimate destination toward which Jesus gradually moves. But first Jesus carves out safe space for the grieving sisters. In addition to being incredibly relevant from a trauma lens, this also contributes to another key yet often missed OT allusion for John 11. It will take a few steps to make this clear, but they are necessary steps to get us to the most significant allusion of all that takes place at the tomb.

Exodus Typology

(1) Movement: In the account of the ten plagues in Exodus, Moses and Aaron repeatedly move in and out of Pharaoh’s court.9 While this might seem like a stretch, I personally hear echoes in the repeated movements in John 11 (as well as the repeated movements in and out of Pilate’s headquarters in John 18-19). There is even a possible echo in the way the movement pattern climaxes before/after the final sign:

Exodus 10:28-29 (between the 9th and 10th plague) Pharaoh said to Moses, “Leave me! Make sure you never see my face again.” Moses replied, “As you have said, I will never see your face again.”

John 11:54 (after the final 7th sign) Jesus therefore no longer walked openly among the Jews but departed from there to the countryside near the wilderness, to a town called Ephraim, and he stayed there with the disciples.

In Jewish memory, the danger the Johannine Community associated with Jerusalem/Judea could find a natural echo in Pharaoh’s court/Egypt.

(2) Safe place: I wonder if “the place” where Jesus meets Martha and Mary bears some resemblance to Goshen. In the fourth plague of flies (Exodus 8:22) and the seventh plague of hail (9:26), the Israelites are kept safe in Goshen. Even though there isn’t a parallel in these specific plagues, Goshen is mentioned twice overall as a refuge for Israel, and “the place” is mentioned twice in John 11. Even if this is a stretch, it’s an intriguing possibility.

(3) Signs: The language of “signs” in John 1-12 brings forward Exodus typology where the plagues against Egypt were described in the Greek Septuagint using the same word for “sign” in John, sēmeion. While it’s unlikely that all seven of the Johannine signs are connected to the ten plagues, some certainly are. The final two signs in John match the final two plagues in Egypt. The ninth plague of darkness is inverted in Jesus giving sight to the man born blind, and the tenth plague of killing the firstborn males is inverted in Jesus raising Lazarus (which leads to Jesus dying as the firstborn paschal lamb, the very sacrifice that protected the Israelites).10

Let My People Go

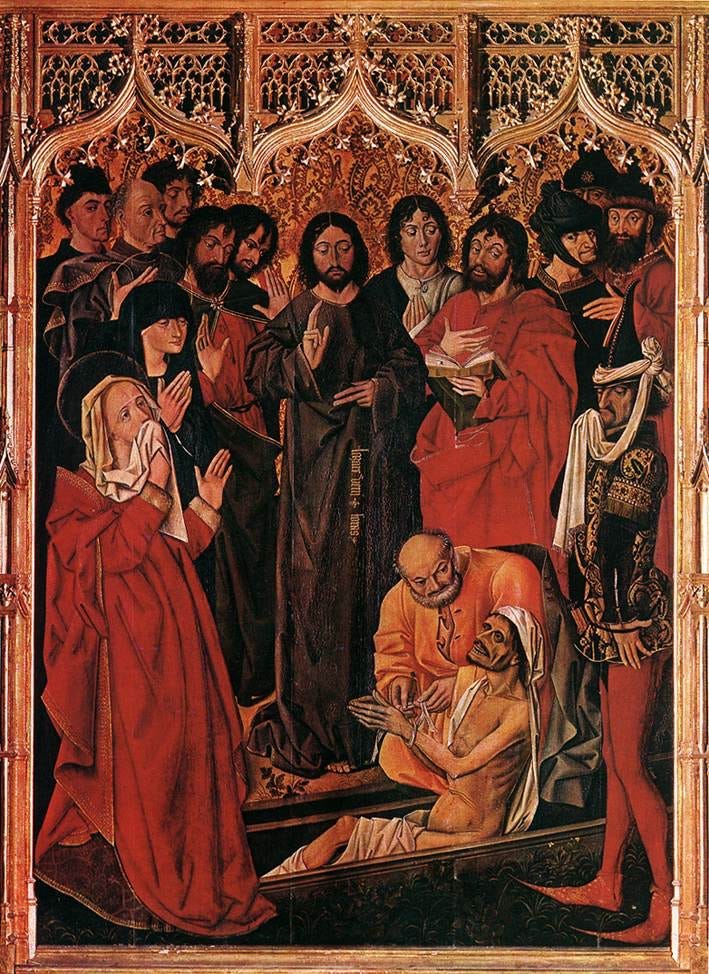

All of this Exodus typology builds to a similar crisis moment in the final plague and John’s final sign. While there isn’t exact verbal parallel in the Greek, the command of Jesus in 11:44, “let him go,” is synonymous with the repeated command from Moses to Pharaoh: “let my people go.”11 This is where everything has been heading all along. The actual act of Jesus raising Lazarus is overflowing with echoes of the Exodus.

Jesus’ command in v. 44 is plural. But who is the “them” whom Jesus commands? It is the “they” who removed the stone (v. 41), the plural object of Jesus’ command to “remove the stone” (v. 38), and the plural “you” Jesus addresses in v. 34: “Where have you [all] put him?” The only possible answer is “the Jews,” specified in vv. 36-37. In other words, Jesus commands “the Jews” to “let him go.” It just so happens that the word Jesus uses, hypagō, only occurs one time in the Septuagint, in Exodus 14:21 where “the Lord drew off [hypagō] the sea.” This is after the Israelites have already left Egypt but still within the overall Exodus event, and adds to the likelihood that an original Jewish audience would have made this connection.

Jesus’ command to Lazarus, “come out!”, might also be an allusion to Ex 3:10, the only place I found in the Septuagint where those two words, deuro eksō, occur together: “And now come [deuro], let me send you [Moses] to Pharaoh, king of Egypt, and you will bring [eksakseis] my people, the sons of Israel, out of the land of Egypt.”

Additionally, while the burial clothes used for Lazarus were typical for Jewish culture, an original audience may have also heard echoes of Egyptian custom. Again, this can work because of the “deep plain sense” of John:

“This unbinding may actually echo an idea dear to the Egyptian culture and depicted on the lid of an ancient sarcophagus: the resurrected human person stands erect, with outstretched arms horn which the strips dangle, with which the dead body had been wrapped. The Egyptians wrapped the body with strips of cloth just for the transition period or travel horn this world to the other world; once the person has arrived in the next world, the wrapping was taken off. The resurrected Lazarus, one may assume, also belongs to a new world—that of the Christian community.”12

In light of all of this, consider Smith’s comments on “the Jews” and the Exodus typology:

“‘The Jews’ play a highly stylized role in the gospel which is quite similar to that of Pharaoh, as the representative of the Egyptians, in the Exodus account; both are consistently represented as opponents of the deity and are characterized by their lack of unbelief [sic] in the signs which the deity performs.”13

Just like Pharaoh’s heart was still hardened after the final plague (Ex 11:10), so too in John “they were unable to believe” even after Jesus’ final sign, because “He has blinded their eyes and hardened their hearts” (John 12:39-40).

A New Exodus

Ok, so what? 2,000 words in and I’m only just now getting practical. But that’s how John works. As David Ford testifies, “Rereading John year after year, I have found that the adverb that fits best is ‘slowly.’ John requires an abundance of time.”14 By this point, my hope is that you, dear reader, can take the Johannine baton and run with it yourself and with your friends and church community. But here are some final closing thoughts for this series.

As biblical scholars have observed in other parts of the New Testament, John is signaling a “New Exodus.” However, unlike some new exodus theologies I’ve read, where rescue from Egypt is equated solely with rescue from sin, John’s account is decidedly not limited to “spiritual” matters. Yes, Jesus is the new and better paschal lamb who takes away the sin of the world, but he is also the new and better Moses who rescues his disciples from the stench of dead religion. Even supposedly orthodox religion.

“The Jews” have been cast as a type after Pharaoh and the Egyptians. So when Jesus says “Let him go,” he doesn’t just mean “literally take off Lazarus’ literal burial wrappings.” The command to “unwrap” him would have sufficed for that. No, more is going on here. Lazarus, as a representative type for early Christian leaders and traumatized Christians, is called by Jesus to freedom from an oppressive and unjust religious system. It is a new exodus. But it is not only a spiritual exodus. It is spiritual, but in the same way that the Exodus was spiritual, and also social, political, and cultural liberation. Because Jesus was not speaking to Lazarus. He was speaking to “the Jews.” The system. Just like the command to “Let my people go” was directed at Pharaoh, Jesus’ command to “Let him go” is for abusive pastors, bully pulpits, and toxic church systems. Instead of finding ways to blame spiritual abuse victims and pressure them back into one’s fixed idea of church, the church should be in the business of unbinding the wrappings of abuse and trauma caused by the church.

If there is any hope of that happening, maybe it is found in the fact that “many of the Jews who came to Mary and saw what he did believed in him” (11:45). Maybe for the Johannine Community these believing Jews represented people who didn’t see Lazarus the way the religious leaders did; maybe they saw him as one who could be welcomed instead of a threat to their power and control (12:10-11, 17-19).

Granted, John goes on to say, “Nevertheless, many did believe in him even among the rulers, but because of the Pharisees they did not confess him, so that they would not be banned from the synagogue. For they loved human praise more than praise from God” (12:42-43). But I like to believe that Nicodemus was one of those Jewish rulers who contributed to the healing of trauma caused by his fellow rulers and teachers. After all, he put the burial wrappings on Jesus (19:40). What better way to make amends for failing to prevent spiritual abuse (7:50-51) then to repentantly care for the one he failed to protect? Instead of binding dead bodies in burial cloths, present day Nicodemus’ can repentantly unbind religious trauma survivors from unrealistic expectations, and let them go to follow Jesus in whatever way he calls them, as Pharaoh said to Moses: “He summoned Moses and Aaron during the night and said, ‘Get out immediately from among my people, both you and the Israelites, and go, worship the LORD as you have said’” (Ex 12:31).

One consistent theme I hear from spiritual abuse survivors is the need for safety. Perhaps “safe place” and “safe space” is not as cliche and “woke” as some would have us think. If “safety is the treatment,” as Stephen Porges puts it, then creating Jesus-like safe places might be delivery system for that treatment.

Quote from David Ford

“‘Unbind him, and let him go.’ The command is clear and practical. It also bursts with further meaning. The astonishing, life-giving event has occurred; now others are needed to join in making it effective. Even after coming to believe, having been ‘born... of God’ (1:13), ‘born of water and Spirit’ (3:5), or having heard the voice of the shepherd calling us by name (10:3-5), we may still need to be liberated from beliefs, attitudes, habits, addictions, constrictions, traumatic experiences, self-images, or whatever else hinders full living, keeping us bound up in things that smell of death and deprive us of freedom; and that liberation usually needs the attentive help of other people. ‘Unbind him, and let him go’ is a watchword for love in action.”15

Question

Please add to this exploratory study of John 11, religious trauma, and contemporary experience. What else strikes you? What else do you see in John 11? What can you take from this series and apply for yourself and/or your church/community?

Mark W. G. Stibbe, “A Tomb with a View: John 11:1-44 in Narrative-Critical Perspective,” New Testament Studies vol. 40 (1994), 43.

See Edwdard Wong, “Representations of Trauma in the Fourth Gospel,” PhD Dissertation (Edinburgh: The University of Edinburgh, 2023), 71-84.

Also, please, please always remember that “the Jews” in John is an ideological term, not an ethnic one. Imagine not having the phrase “Christian Nationalist,” and needing to differentiate yourself as a Christian from nationalistic Christianity. John’s strategy, and the Johannine Community’s, is analogous to letting the Christian Nationalists have the name “Christian,” and only ever (or almost always) associating “Christian” with evil, sin, violence, and imperialism.

Movement is surprisingly emphasized in John 11, once one slows down to see it. It’s easier to list verses that don’t reference movement and space/location, but here are all the ones that do: 10:39-40; 11:3, 6, 7, 9-11, 15, 16, 17, 18-19, 20, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 34, 38, 44, 45, 46, 48, 54

Wong, “Representations of Trauma,” 83.

Interpreters and historians have not been able to definitively identify this location.

Mary Coloe, God Wells With Us: Temple Symbolism in the Fourth Gospel, 165.

Ford, The Gospel of John, 1.

Some interpreters, including Paul Minear, read the sister’s message to Jesus at the beginning of this story as an attempt to avoid detection by “the Jews”. He writes, “Although the sisters try to keep their meetings with Jesus a secret, these Jewish neighbors foil their efforts and take the center of the stage when Jesus openly challenges the power of death. The narrator describes their attitudes as an amalgam of truth and error. Truth in that they express their affection for this Bethany family and in that they recognize Jesus’ love for Lazarus, which the narrator had also stressed (11:3, 5, 11). Error, in that they had supposed that Jesus’ tears represented love-induced grief rather than indignation.” John: The Martyr’s Gospel, 120-121.

See Exodus 4:19, 24, 27; 5:1, 15, 20, 22; 6:10; 7:10; 8:1, 8, 12, 20, 25, 30; 9:1, 7, 10, 13, 27, 29, 33; 10:1, 3, 6, 8, 11, 16, 18, 24, 28, 29; 11:8; 12:31.

See Robert Houston Smith, “Exodus Typology in the Fourth Gospel,” The Society of Biblical Literature and Exegesis (1962), 336-337.

See Ex 5:1 etc.

Bernhard Lang, “The Baptismal Raising of Lazarus,” Novum Testamentum 58:3 (June, 2016), 313.

Smith, “Exodus Typology,” 341.

Ford, The Gospel of John, 435.

Ford, The Gospel of John.

What a different way to read this story, through the eyes of Lazarus, and then spiritual abuse/harmful religious systems. This way of rereading John is new to me, but very compelling! As one healing from church harm over the 2yrs, this hits very close to home, and I can echo the need for a safe space. That is real! I hadn’t understood that before, but the sense of unsafety can be very destabilizing, especially from a community/people where one expects acceptance, warmth, even love.

I suspect that healing will come in the safe spaces you mention. Perhaps the safe spaces aren’t only the delivery method, but also the treatment…when the safe spaces are ones where the focus is on Christ, His character, words, and actions. As I ponder who He is in these stories and also as I encounter Him in safe spaces I’m finding, it’s Jesus that is healing me….the Good Shepherd leading me (ekballo) into greener pastures again, after having been expelled (both literally and figuratively) by church leaders (a la John 9/10). In safer church spaces where the gospel is preached and ministered in safer ways, and in spaces like this where the injustice of church harm is called out and recognized and Jesus’s tears and weeping in its face is highlighted, more healing comes.

Thank you for opening yet another safe space. May we all be a part of bringing safe spaces for our brother and sisters who need them!