Have you ever sat at a table and eaten a meal with a betrayer? Have you ever dined with a close friend who later stabbed you in the back? I have. Many times. Many meals. Over many years. With a shepherd and his family. I remember the evening meals of delicious, mouth-watering steaks, and breakfasts with buttery-sweet pancakes, savory eggs and greasy bacon. I remember eating chicken that for the first time in my life was tender and juicy (growing up with my mother’s chicken which was always overcooked and dry, I just thought that’s how all chicken was and stopped eating it for years). That savory grill-charred barbecue chicken was really the side dish to the main meaty course of a private theological meal for my wife and I on the distinctives of presbyterianism and the Westminster standards.

It was also that shepherd who — 12 years after that meal of hearth-fired poultry and heart-warming presbyterianism — fired my wife for daring to speak out against cover up of sexual abuse committed by a church elder. While I’m not always consciously aware of it today, when I sit down for food and fellowship with close friends, there is a part of me now that wonders, “Is this safe?” I thought there was safety before, and was wrong. How much trust should I feel in this new meal? How much should I question my fear? How much should I respect my fear? What do I do when the reformed theology with which I have been nourished for almost 20 years now tastes of bitter betrayal?

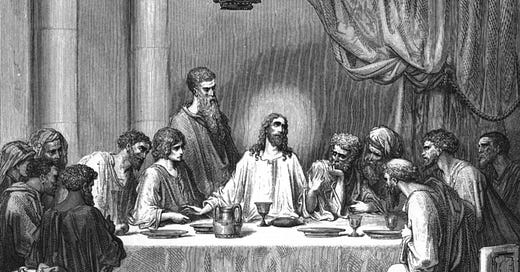

These are some of the thoughts, feelings, images and sensations that come to mind when I read John 13:18:

“I’m not speaking about all of you; I know those I have chosen. But the Scripture must be fulfilled: The one who eats my bread has raised his heel against me.” (CSB)

This may sound like strange material for an Advent reflection. Here’s the connection. The Gospel of John cannot be read properly without tuning in to symbolic images and the sensations they activate through associative memory.

Dan Siegel has a helpful acronym I often use for myself and with my clients: SIFT, which stands for Sensations, Images, Feelings, and Thoughts. SIFT is a way of practicing attuned awareness to one’s internal world. Attending to SIFT helps settle into embodied experience, and it’s a helpful way of “sifting” through the interaction between experiential memory and the text of the Fourth Gospel.

The Incarnational Key

In this season of Advent, the incarnation provides a hermeneutical key for opening the door to a fresh way of reading John.

Adrienne von Speyr takes four pages of her commentary on John to explore the incarnation using the refrain, “The Word was made flesh means...”1 It’s a striking refrain when repeated multiple times. The Word was made flesh surely means more than we will ever fathom. Which is one of the implications of the incarnation: God in a human body, who can fully understand that? Speyr says something similar with how John approached the revelation given to him by Jesus:

“But when he remains with this word [ie, meditates on it], he becomes ever more aware of its content, which goes much deeper than he first surmised. It provides ever-new amazement.”2

The incarnation of Jesus grounds the “ever-new amazement” provided by John’s Gospel.

It is possible for us to read John (indeed, all of Scripture) in such a way that we sense the text. This is not really anything new, as Christian spirituality has a long history of connecting physical senses with spiritual senses.3 But it is necessary for us to reappropriate this approach in a time when Western culture is prevalently disembodied, and when church culture dominates dismemberment through spiritual abuse. Recently scholars have been paying closer attention to the sensory qualities of the Gospel of John. I will have more to say about these works in my book, but what I’ve written here was chiefly inspired by Dorothy Lee4, Jeannine Marie Hanger5, and Sandra Schneider.6

In John 13:18, Jesus himself modeled this kind of sensory associative engagement with Scripture. To use Speyr’s phrase again, The Word was made flesh means that Jesus has a memory just like every human, a memory which implicitly draws on past experience and makes associative connections between the past and present. So, is it possible that Jesus’ appropriation of Psalm 41:9 to interpret Judas’ betrayal was also mediated by sensory memorial associations with David’s psalm?

What other associations might Jesus and John be inviting us to make with the eating of bread and betrayal? That is a hermeneutical question, but I also intend it as a psychological question. Following Hanger’s guidance, we can imitate the original audience of John in two ways: first, considering what associations the symbolic images created for them in light of their religious culture and knowledge of Scripture (eg, passover, Exodus, temple sacrifice, etc.); and second, considering how the symbolic sensory images connect with their own personal experience (i.e., eating physical bread the day before Jesus’ discourse on the bread of life).

The path through this meditative approach is not simply or solely explicit memory. It also engages implicit embodied memory, in the same way that smelling biscuits and gravy always reminds me of Sunday mornings at my grandma’s house in Mission, KS. One route to this embodied memory is imagination: using one’s mind to focus attention on sensations, images, thoughts and feelings.

As I read John 13:18 and see an image of myself at that pastor’s table, I feel a tightness in my stomach. It’s as if I asked for bread, and got a stone instead (Matthew 7:9). There is now confusion and danger where before there was simple trust. And I wonder, did Jesus feel any of that as well? Did Judas’ betrayal cause him psycho-physiological pain? The Word was made flesh means that is certainly possible.

As I meditate on the meal scene of John 13 and following the path of sensory associative memory, I next think of John 21 when Jesus feeds his wayward disciples fish and bread. Remember, John 13 was the last time we read about the disciples eating bread. I imagine each one of them immediately recalling that meal, if not when they saw the bread and fish laid out (21:9), then when they tasted and swallowed the food (21:13). As Ed Welch observes, there is also a particularly strong association for Peter. Jesus cooked the fish on a charcoal fire, the same word used in 18:18 when Peter denied Jesus while standing around the fire with the slaves and guards in the high priests’ courtyard.7 And for all the disciples, Jesus knew they needed a new association and memory for meals together. Meals marked, not by betrayal and cold death, but generous compassion and the warmth of new life.

New Meals, New Memories

That is exactly what Jesus offers every one of God’s children in the Lord’s Supper. The memories that get activated by Jesus offering his body and blood are numerous and unique to each individual and culture. But for spiritual abuse survivors, there is a unique challenge and healing, to which

testifies so powerfully. She writes about the time she and her husband served communion to the pastor who harmed them, and how that memory was activated the first time receiving communion at a new church.“After not being able to even step foot inside a church for months after that, it was compassion that carried me back. As I swallowed the wine-dipped bread, I looked up through my teary storm cloud eyes and found the priest’s eyes looking back into mine with kindness. This was resolution. This was absolution. This was the circle of communion enfolding my hurt with love. Communion was giving me courage to trust there could be compassion in church again.”8

What a beautiful picture of how embodied contact with Jesus can heal embedded memories of trauma. Hearing K.J.’s experience of embodied healing gives me hope. I see a wounded truth-teller tasting the already presence of Christ, encouraging me while my family is mostly in the not-yet of Advent waiting.

Though my presence at the communion table has been minimal this year, I have sensed the presence of Jesus with me in bodily form by reading slowly through John 6 (where Jesus feeds the crowd and calls himself the Bread of Life), John 13 (where bread and betrayal are linked together in trauma), and John 21 (where the risen Jesus generously feeds his fearful, doubting disciples). The Gospel of John sustains my hope that there is always a table where I and my family are welcome. We have a friend who is faithful to feed us with rich food.

I can even dare to hope that the invitation to “eat the flesh of the Son of Man and drink his blood” (John 6:53-58) calls forward the joyous invitation of Song of Songs 5:1. If the Jewish people historically read the Song of Songs every Passover, then this verse might very well be in the background of John 6 and John 13 (each of which begins with the mention of Passover), also bringing together the resurrection scene of Jesus with Mary Magdalene in John 20, and the meal invitation from Jesus to the disciples in John 21. In a word, there isn’t just a promise of a table and a meal, but a party. Here is Song 5:1 in English translation of the Septuagint, which mentions bread, unlike the Hebrew text:

I have come to my garden, my sister, my bride; I have gathered my myrrh with my spices; I have eaten my bread with my honey; I have drunk my wine with my milk. Eat, mates, and drink, and be drunk, brothers and sisters.

It settles my stomach and calms my heart to hear that the incarnate, risen Christ has transformed the bread of betrayal into the bread of blessing and belonging.

What he first ate and drank himself in the garden and on the cross he now offers for healing and celebration.

Though just a gentle breeze that rarely even moves the hair on my arm, I sense the Spirit’s invitation to remember the future by imagining the taste of the water of life (Rev. 22:17).

This settling, this sensing in the waiting, comes from chewing and digesting these words through a sensory, imaginative reading, a way of reading which is available to us because of the incarnation.9 As Peter put it in John 6:68, “You [Jesus] have the words of life.” These words are meant to be eaten, and that calls for sifting through our embodied experience with the Word.

Quote from Bruno Barnhart

As the waters of new life disappeared into your depths, your life became once again, apparently, an ordinary life. In your own place you had worked all through the night without result when a lone figure called out to you from the distance. You cast as he suggested, and suddenly the nets were filled with fish. It was he! It was like the first time, at the wedding, when he made wine. It was like the time when he broke the bread beside the sea and fed the five thousand…Again and again you will pass through these waters and meet him upon the shore. Again and again you will experience the dawn of his coming and be filled with his bread and fishes. And it will always be as that first time. The sun has risen once again; the fire burns within your hearts as you walk together along the road, thinking ever of him and all the things he said and did. In the fire and light of that Easter night—his fire and light that are within you through your baptism—all of the scriptures lie open to you now. As you follow him, yet you remain ever here: here by the water and the fire, the bread and the fish, as the sun rises upon the shore.10

Question

There are popular Bible reading plans/methods that offer questions to be asked of Scripture, eg, is there truth to be believed, command to be obeyed, prayer to be prayed, etc. Try adding these questions to your regular Bible reading: what do you sense in your body as you read? What memories come up for you if you imagine your senses of sight, hearing, touch, taste, and smell? How might the Spirit be calling up those memories for new and deeper healing?

The Word Becomes Flesh: Meditations on John 1-5 (Ignatius Press, 1994), pp. 117-120.

The Word Becomes Flesh, p. 11.

As noted by Hans Urs von Balthasar in The Glory of the Lord: A Theological Aesthetics: Seeing the Form, many theologians throughout history employed the five physical senses of sight, touch, hearing, taste and smell as way of exploring the multifaceted manner of experiencing God. Just two examples he cites are Augustine in X.6 of Confessions, and Thomas Aquinas in his commentary on Philippians 2.

Dorothy Lee. “The Gospel of John and the Five Senses.” Journal of Biblical Literature, vol. 129, no. 1, 2010, pp. 115–27. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/27821008.

Jeannine Marie Hanger. Sensing Salvation in the Gospel of John: The Embodied, Sensory Qualities of Participation in the I Am Sayings. Brill, 2023.

Sandra Schneiders. Written That You May Believe: Encountering Jesus in the Fourth Gospel. Herder & Herder, 2003.

Ed Welch, Shame Interrupted: How God Lifts the Pain of Worthlessness and Rejection, p. 200.

K.J. Ramsey, The Lord Is My Courage (Zondervan, 2022), p. 205.

I am increasingly convinced that the sensory-rich quality of John’s Gospel was heavily influenced by the Song of Songs (although it is also a general Hebrew characteristic). As mentioned above, Passover is a recurring contextual element for John, more so than the other Gospels, and the tradition of reading Song of Songs before and/or during Passover is highly suggestive.

Bruno Barnhart, The Good Wine: Reading John from the Center, p. 357-358.

This article was soothing to my soul